Beach Education And Conservation of Habitat (BEACH) Program

Our diverse and productive shorelines are under threat from multiple sources, including pollution, overland flow erosion, storm drain outfalls, garbage, sea-level rise, climate-related storm activity, and backshore development. Without conservation, restoration, and careful planning, these culturally and ecologically critical areas will be lost.

Our Beach Education and Conservation of Habitat (BEACH) Program provides Victoria area residents with opportunities to gain hands-on experience in shoreline conservation and protection. The program addresses these threats and supports environmental stewardship through shoreline restoration, environmental education, and community science.

Although many people know their beaches intimately, they don’t always know how a beach was formed and that it is constantly changing. Along with education about dynamic beach processes, we teach stewards to identify developing or imminent environmental threats. We also train and facilitate a comprehensive community science program that identifies which beaches are important forage fish habitat or at risk from invasive European green crabs. Together, armed with this knowledge, we are better able to help mitigate threats to beaches by lobbying and supporting planning and restoration activities.

1) Forage Fish Beach Spawning Surveys

What are forage fish?

Forage fish, often called prey fish or bait fish, are small schooling fish that play a crucial role in the marine food web as food, or ‘forage’, for a multitude of other species. There are 7 common species of forage fish in BC: Pacific sand lance, surf smelt, Pacific herring, Pacific sardine, Northern anchovy, eulachon, and capelin.

Forage fish are a vital link between low and high trophic levels, feeding on phytoplankton and zooplankton and transferring this energy to salmon, seabirds, marine mammals, and humans. For example, forage fish comprise 60% of adult Chinook salmon summer diets, which in turn comprise 80% of southern resident killer whale diets. With both Chinook salmon and southern resident killer whale populations in decline, having healthy populations of forage fish on our coast is critical to ensuring the overall health of the Salish Sea marine environment.

In addition to their ecological value, forage fish are also commercially, recreationally, and culturally important around the world, currently accounting for over 1/3 of overall marine harvest by weight.

What's the problem?

Despite being relatively abundant, cumulative effects from predation, poor water quality, habitat modification and degradation, overfishing, and climate change make forage fish susceptible to dramatic population fluctuations. Expand on each box below to learn more about the threats these fish face.

Surf Smelt and Pacific Sand Lance

Unlike some of the other forage fish species found on our coast that spawn in offshore waters, nearshore waters, or river systems, surf smelt and Pacific sand lance utilize the upper third of the intertidal on sand-gravel beaches for spawning. Individuals approach the water line on a high tide and deposit adhesive eggs on sand and pea gravel sediments, which then disperse along the beach with wave and tidal activity and can be buried 2-15 cm into the sediment.

Surf smelt, reaching lengths of up to 22 cm, spawn year-round on sediments comprised of pea gravel with a sand base. Eggs incubate within the sediment for roughly 12 days in the summer and up to 20 days in the winter. For summer spawning populations, shade from overhanging vegetation and freshwater seepage act as important means for lowering egg desiccation risk. The newly hatched larval fish are roughly 3 mm in length with a small yolk sac attached, and swim off at the next high tide.

Pacific sand lance, reaching lengths of up to 28 cm, spawn only during the winter season (roughly November-March) on sediments comprised of pea gravel with a sand base, but also extending into pure sand as well. They also tend to spawn at slightly lower elevations than surf smelt. Eggs incubate within the sediment for up to 3-4 weeks. Like surf smelt, the newly hatched larval fish are roughly 3 mm in length with a small yolk sac attached, and swim off at the next high tide.

Forage fish are undergoing a 'coastal squeeze', experiencing the effects of shoreline development on land and climatic conditions from the sea, diminishing the quality and quantity of beach habitat for spawning.

Our Program

While Washington State has carried out forage fish beach spawning surveys along their coastline since 1972, surveys in British Columbia are underdeveloped. As a result, knowledge is limited on Pacific sand lance and surf smelt abundance, distribution, and use of intertidal beaches for spawning in British Columbia’s portion of the Salish Sea.

Our volunteer-run forage fish beach spawning surveys help identify and monitor active surf smelt and Pacific sand lance spawning habitat through the collection of sediment samples from locations with favourable habitat characteristics. Positive detections for spawning help us to understand forage fish movement, spawning behaviour, how human actions may be affecting them, and what changes occur in marine food webs as forage fish continue to face threats to their populations.

The valuable data we collect from these forage fish beach spawning surveys not only address the data gaps in British Columbia, but are important for informing nearshore policies, supporting evidence-based advocacy that push for the protection and restoration of forage fish beach spawning habitat, and contributing to other nearshore research projects throughout the Salish Sea.

Using the menu icon in the top left corner, toggle between layers and explore our sampling sites and where we've found positive detections for surf smelt and Pacific sand lance eggs.

The Coastal Forage Fish Network (CFFN)

In 2022, Peninsula Streams co-founded the Coastal Forage Fish Network (CFFN), a collaboration of individual groups across the BC coast working towards identifying and monitoring forage fish spawning habitat. The network’s vision is thriving stable forage fish populations that can sustain the predators that rely upon them and contribute to a healthy marine food web within the coastal waters of BC. The network is continually growing and includes multiple environmental NGOs, community groups, and First Nations, encompassing hundreds of community scientists.

All of the CFFN's forage fish beach spawning survey data is publicly available in the centralized and open-access online database known as the Pacific Salmon Foundation (PSF) Marine Data Centre, a collaborative program between PSF and the Institute for the Ocean and Fisheries at the University of British Columbia (UBC). PSF also hosts a forage fish dashboard for the CFFN, where users can access resources and explore where spawning has been documented across the BC coast.

Check out the data:

Watch the CFFN's past symposiums below:

2) Shoreline Restoration & Monitoring

Our goal is to restore, conserve, and protect shoreline habitats against their many threats. We help to identify and monitor key habitats, inform policies, and demonstrate ‘soft shore’ approaches, such as removing unnecessary riprap and bulkheads, “nourishing” shorelines with forage-fish-friendly sediments, and using native plants to protect shorelines while maintaining natural sediment and nutrient processes so these places persist for people and nature to enjoy.

Learn more about our restoration projects here:

3) Invasive European Green Crab Monitoring

Native to coastal areas of Europe and North Africa, European green crabs have quickly become one of the top ten most invasive marine species in the world, now spotted on every continent except Antarctica. Brought over to the east coast of North America in the ballast water of ships in 1817, green crab have continued to spread both by natural means (long, drifting larval stage) and human-mediated transportation (ballast water, seafood and fishing gear transport, recreational boaters).

First spotted on the west coast of Vancouver Island in the late 1990s, green crab have slowly been spreading along the BC coast, with well-established populations in Sooke Basin and Clayoquot Sound. Other small detections have popped up in Witty's Lagoon, Esquimalt Lagoon, the Gorge Waterway, Salt Spring Island, Ladysmith, Boundary Bay, Port Hardy, and Haida Gwaii.

Extremely adaptable to a wide range of environmental conditions, green crab are able to quickly establish in a variety of habitats and climates. Once they do, these crabs have a major ecological impact, outcompeting native crab and bird species for food, excavating eelgrass beds during foraging and burrowing, and heavily predating on a number of native species such as clams, oysters, mussels, snails, small fish, and shore crabs. Their impact on eelgrass beds is of particular concern due to their role as critical estuary habitat for outmigrating juvenile salmon.

Once a population of European green crab has established, it's virtually impossible to fully eliminate them. Early detection and prevention of this species in our local waters is key; by getting ahead of the problem and removing individuals before they have a chance to reproduce, we can protect our native populations from this harmful invasive species.

In 2023, Peninsula Streams joined the 'Pacific Region European Green Crab Mitigation and Capacity Development Project', a program developed by Pacific Salmon Foundation and Coastal Restoration Society, and funded by Fisheries and Oceans Canada through their Aquatic Invasive Species Program. This project aims to deliver green crab detection monitoring training and support to coastal communities in priority gap areas across the BC coast. From April to September, we perform monthly trapping sessions at various local sites. A line of 6 traps is set at low tide and left to soak for 24 hours before returning to identify all species—native species are released immediately, while European green crab are not.

4) Beach Cleanups

Did you know that 80% of marine pollution comes from the land? Garbage, debris, plastics, chemicals, and other synthetic materials pose a severe threat to our streams, shorelines, and oceans, endangering sensitive habitats and the diverse flora and fauna that depend on them, including vital species like salmonids.

To tackle this pressing issue, we actively coordinate regular clean-up initiatives at local shorelines in need. These efforts not only aim to physically remove harmful waste but also serve to educate and inspire individuals about the importance of conserving our natural environments. By engaging communities in hands-on conservation activities, we strive to foster a collective responsibility towards protecting and restoring our aquatic ecosystems.

Ready to get your hands dirty?

5) Shoreline Education Program

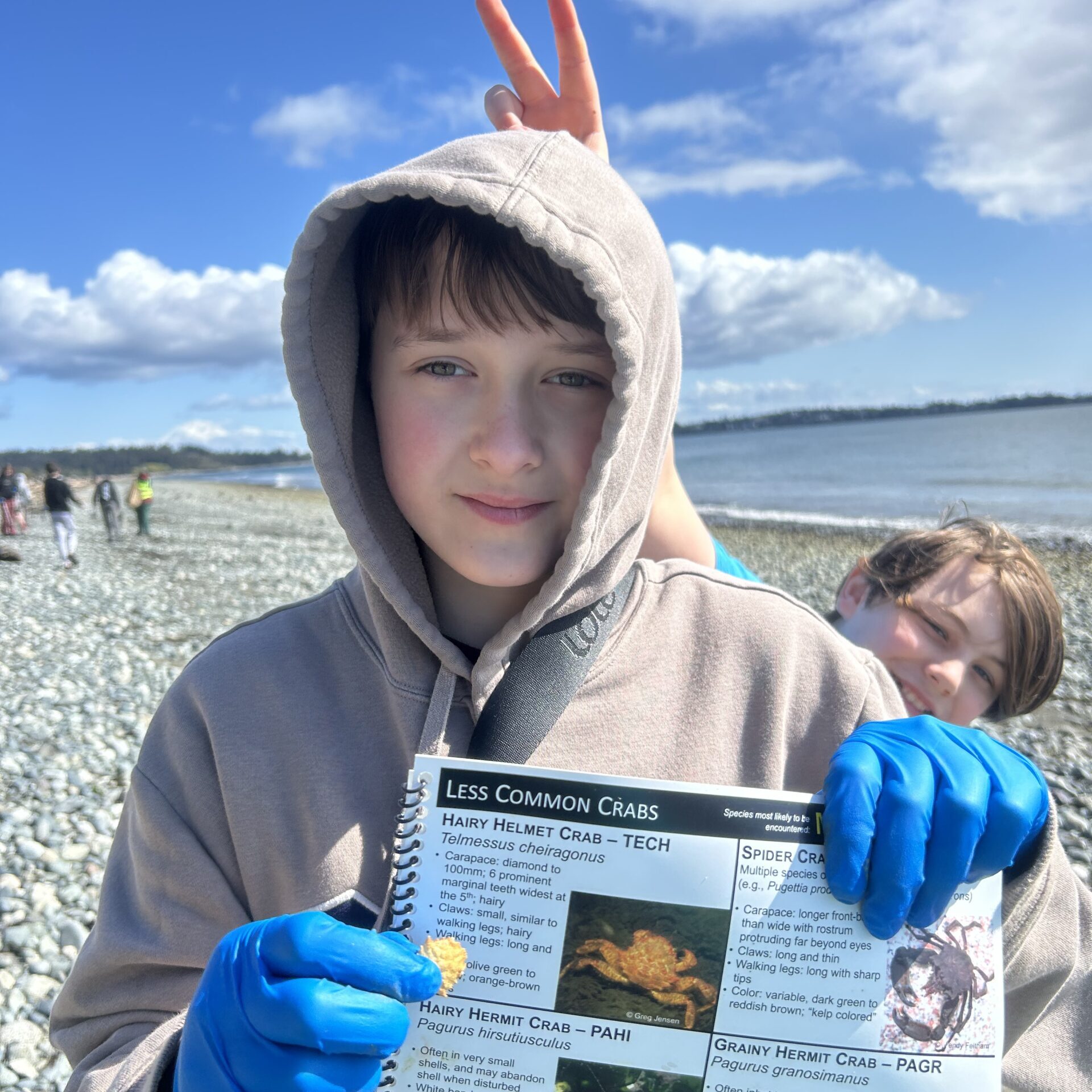

Our Shoreline Education Program brings youth to their nearest beach, where they'll be immersed in hands-on marine science and stewardship activities, learning about forage fish, native and invasive crabs, and human impacts on the health of our shorelines.

This program also gives students a greater understanding of local research and restoration projects and initiatives, helping youth connect their learning to their sense of place, and see themselves as part of a community of shoreline stewards.

choose your own adventure

We adapt our program to different beaches, seasons, tides, schedules, and grade levels. That means each event is unique!

We offer 4 core activities. Your event will likely include 2 or 3 of them, with groups of students rotating between each station. Depending on location, time restraints, and the size of your group, some activities may not be available. But don't worry! We will work with you to create a unique and impactful day of learning, that meets the needs of your group.

Forage Fish Spawning Survey

Students get hands-on experience monitoring for surf smelt and Pacific sand lance. (~30 mins)

Crab Scavenger Hunt

Students learn about native and invasive crabs, and how to identify them. (~20 mins)

Beach Seining

Students will help PSS Biologists as they identify the diverse species in our nearshore marine ecosystems. (~30 mins)

Beach Clean Challenge

Students work in teams to remove garbage from their local shoreline. The largest piece of trash wins the challenge! (~20 mins)

TEACHER TESTIMONIALS

“Our students were super excited about seeing what was living in the waters they see everyday. It was a bit of a big reveal. The net scooping up what looked like just water and then the students getting in close and seeing all these amazing living creatures. And then to top it all off they got to get up close to all the creatures in the viewing containers. It was an amazing experience and I am very grateful for the opportunity to bring this to our classes. The experience was priceless and yet completely accessible because we did not have to pay for it."

Sonya McRae, Teacher

Shoreline Community Middle School

“We had an amazing time with you at Esquimalt Lagoon! The knowledge they gained has been useful in other studies moving forward and was so fun and valuable for me and the students. Thank you again!”

John Dobson, Teacher

Lighthouse Christian Academy

"Our Environmental Systems and Societies 11 (ESS) students really enjoyed learning some field work skills, identifying local marine biodiversity, and learning about all the restoration work from Peninsula Streams. To prepare us for our field work, PSS came to our school to make connections to our curriculum and discuss their environmental projects. Furthermore, PSS’ biologists and educators shared some more resources following our experiences. Our intertidal experience was definitely enhanced by PSS’s experts in the field."

Jennifer Walton, Environmental and Outdoor Educator

St. Margaret's School

"Peninsula Streams has been offering high-quality programming with Parkland Secondary for many years. Their staff are experienced, highly trained, and make outdoor learning fun and engaging! Getting students involved as citizen scientists is a valuable part of their education and keeps them engaged as life-long learners and community leaders."

Erin Stinson, Teacher

Parkland Secondary School

"This is a highly experiential opportunity for the students with unbelievable connections to STEAM education. I love that this training leads to an ongoing service-learning activity that is quite self directed. The students are excited to return to the beach, to do more surveying, and to build a legacy of stewardship and partnership with a specific place and piece of land. What could be more beautiful than that?"

Teacher

St. Michaels University School

"The facilitators have all been excellent and worked well with the students from Grade 9-12. We've always appreciated the ways they engage the students and deep ecological knowledge of the area. We also appreciate when they're willing to share their personal journey toward becoming an environmental educator!"

Erin Stinson, Teacher

Parkland Secondary School